Toward a Regional Legal Framework for Climate-Induced Migration in Southeast Asia: Lessons from Indonesia and the ASEAN Response Gap

ABSTRACT

As climate change accelerates, Southeast Asia faces rising sea levels, floods, and extreme weather that displace millions. Yet legal protections remain inadequate for those forced to migrate due to environmental factors. This research examines the legal vacuum surrounding climate-induced migration in Southeast Asia, using Indonesia as a case study to highlight policy gaps and human costs. It critiques the limitations of current international and ASEAN frameworks, and proposes a rights-based, ASEAN-specific legal framework rooted in climate justice and regional solidarity. The study combines doctrinal legal research with comparative policy analysis, advocating for a reimagining of migration as a humanitarian and environmental justice issue rather than a security threat.

Keywords: Sustainability, Environmental Law, Climate-Induced Migration, Climate Justice, Southeast Asia, Environmental Displacement, Legal Frameworks, ASEAN Law, Climate Justice, Human Rights

Introduction

1.1 Background and Context

In recent years, Southeast Asia has emerged as one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable regions. From typhoons devastating the Philippines, to prolonged droughts in mainland Mekong, and rising sea levels threatening Indonesia’s coastal communities, the impacts of climate change are no longer hypothetical but deeply existential. Indonesia, an archipelagic state with over 17,000 islands, is particularly exposed to sea-level rise and coastal erosion. Research published in Nature Communications estimates that as many as 23 million Indonesians could be living below annual flood levels by 2050 if carbon emissions remain high.[1] The capital city, Jakarta, is already sinking due to a combination of groundwater extraction, urban overdevelopment, and rising seas.

Despite these dire projections, legal protections for people displaced by climate change remain fragmented, undefined, and, in most ASEAN states, legally non-existent. The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol do not recognize environmental degradation or climate events as valid grounds for refugee protection.[2] Moreover, ASEAN’s principle of non-interference and the absence of a robust, rights-based regional human mobility framework create a structural vacuum for responding to climate-induced displacement.[3] While Indonesia has taken some steps to address internal displacement through its disaster risk reduction framework, its efforts are largely reactive and lack a cohesive, forward-looking legal mechanism.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

The absence of a unified legal framework in Southeast Asia to address climate-induced migration leaves millions in legal limbo. As slow-onset environmental degradation and sudden disasters increasingly drive people from their homes, ASEAN’s institutional response remains largely rhetorical or ad hoc. While several policy discussions have acknowledged the risks of displacement, there is still no binding regional agreement or action plan to protect those affected. The result is a growing normative and humanitarian gap, especially in states like Indonesia that face significant internal and cross-border mobility pressures.

1.3 Research Objectives

This research aims to critically assess the legal and institutional gaps in Southeast Asia concerning climate-induced migration, using Indonesia as a case study. It also seeks to:

Explore the viability of a regional legal framework to address climate mobility within ASEAN;

Analyze Indonesia’s national legal, environmental, and disaster management responses;

Identify normative lessons and policy tools that could inform a rights-based, regionally cohesive approach to climate-induced migration.

1.4 Research Questions

How does Indonesia currently respond legally and institutionally to climate-induced internal and cross-border migration?

What are the key legal and policy gaps at the ASEAN level concerning climate-induced migration?

What lessons can be drawn from Indonesia’s experience to inform a regional legal framework within ASEAN?

How can such a framework be shaped to balance state sovereignty with human rights and environmental justice?

1.5 Significance of the Study

This study speaks to the urgency of developing legal innovations at the intersection of climate justice, human rights, and regional integration. While climate-induced displacement is a global concern, Southeast Asia’s institutional inertia demands focused scholarly and policy attention. By centering the Indonesian experience, this research contributes to building a contextualized yet scalable model that could inform regional law-making processes. Furthermore, this research attempts to bridge the often-isolated discourses of environmental law, migration studies, and Southeast Asian regionalism.

1.6 Methodology and Scope

The study adopts a doctrinal legal research methodology combined with comparative policy analysis and normative critique. Primary sources include Indonesian national legislation, ASEAN charters and declarations, relevant international treaties, and climate adaptation frameworks. Secondary sources include journal articles, NGO reports, and empirical research on migration patterns and climate vulnerability in the region. The scope is limited to internal and regional (intra-ASEAN) migration linked to climate events, rather than international migration to the Global North.

1.7 Structure of the Paper

This paper is organized into six chapters. Following this introduction, Chapter 2 provides a literature review on climate-induced migration and regional legal responses. Chapter 3 critically examines Indonesia’s national legal responses and climate policies. Chapter 4 assesses ASEAN’s legal architecture, highlighting key institutional and normative gaps. Chapter 5 proposes a conceptual framework for a regional legal response, drawing from Indonesia’s case and other comparative insights. Finally, Chapter 6 offers conclusions and policy recommendations for integrating climate justice and human security into ASEAN’s future agenda.

2. Conceptual and Legal Foundations

Understanding the legal, ethical, and conceptual terrain surrounding climate-induced migration is critical to designing a robust regional legal framework for Southeast Asia. This section lays the groundwork by examining how climate-induced migration is defined and framed within current literature, analyzing its human rights implications, and critically assessing international legal regimes that, directly or indirectly, engage with this complex phenomenon. It then identifies the most significant normative and legal gaps in international law, setting the stage for a regional analysis in subsequent chapters.

2.1 Defining Climate-Induced Migration

The term “climate-induced migration” does not have a universally agreed-upon definition in international law. It broadly refers to the movement of individuals or communities driven by the impacts of climate change, including but not limited to rising sea levels, desertification, extreme weather events, droughts, and ecosystem collapse.[4] Such migration may be internal or cross-border, temporary or permanent, voluntary or forced. What complicates the terminology is the often multi-causal nature of displacement, wherein climate stressors interact with social, political, and economic vulnerabilities.[5]

For instance, a coastal community in Indonesia may relocate due to increasing tidal floods, but the decision may also be influenced by lack of infrastructure, economic decline, or loss of agricultural viability. These overlapping drivers render the migration neither strictly environmental nor strictly economic, but a hybrid form of forced mobility that defies conventional legal categories.[6]

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has introduced terms like “environmental migrant,” “climate migrant,” and “environmentally displaced person,” each with varying emphasis on voluntariness and causality.[7] However, without a binding definition in international law, states remain under no formal obligation to recognize or protect these groups. Furthermore, classifying “climate migrants” challenges traditional legal taxonomies. These individuals often fall between categories of “refugees,” “internally displaced persons,” and “economic migrants,” reflecting constrained agency rather than pure voluntariness. This grey zone requires new legal imagination beyond current binaries.

Moreover, the language of “migration” often implies agency, while “displacement” conveys compulsion. In contexts such as Southeast Asia, where socio-economic precarity is high and adaptation resources are limited, many people face forced immobility—they are too poor to move or lack the legal and logistical ability to relocate.[8] Thus, any legal or policy response must be attentive not only to those who move, but also to those who cannot.

2.2 Climate Justice and Human Rights

Climate-induced migration cannot be fully understood without placing it within the broader framework of climate justice and human rights. Climate justice recognizes that those most affected by climate change—often poor, Indigenous, or marginalized populations—are typically the least responsible for its causes.[9] In the Southeast Asian context, small island communities, low-lying coastal populations, and rural farmers are facing existential threats, while industrial emissions are largely driven by global supply chains and urban economies.

From a human rights perspective, climate-induced displacement implicates a wide array of entitlements protected under international law, including:

The right to life, health, and an adequate standard of living under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR);[10]

The right to housing, including protection from forced eviction;

The right to protection from arbitrary displacement, especially under soft law instruments such as the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement;[11] and

The right to remedy and participation, particularly for Indigenous communities whose traditional lands are threatened by environmental degradation.

Yet, for millions across Southeast Asia, these rights remain aspirational rather than enforceable, particularly when displacement crosses national borders. In the absence of legal recognition or regional cooperation, displaced persons often lack access to basic services, legal status, or durable solutions.[12] The invisibility of climate migrants within ASEAN’s legal discourse is not just a gap in governance, it is a profound moral failure rooted in structural inequality.

2.3 International Legal Frameworks

Existing international law provides limited but relevant protections for climate-displaced persons. These frameworks fall into three overlapping categories: refugee law, human rights law, and non-binding or “soft law” instruments such as global compacts and adaptation frameworks.

2.3.1 The 1951 Refugee Convention and Its Limits

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, as extended by the 1967 Protocol, defines a refugee as someone who, “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion,” is outside their country of nationality and unable to return.[13] Notably, this definition does not encompass people displaced by natural disasters or climate change, regardless of the severity of threat.

Several legal scholars, and UNHCR itself, have acknowledged that the Convention is ill-suited to address environmental displacement, especially in the context of slow-onset events such as sea-level rise or drought.[14] While some climate-displaced persons may qualify for refugee status on other grounds (e.g., if environmental degradation is linked to persecution or conflict), these are narrow exceptions rather than systemic solutions. Attempts to reinterpret or expand the definition of “refugee” to include climate-induced displacement have met resistance from states concerned about legal and financial obligations. As such, the Convention remains a foundational but insufficient tool in addressing the realities of climate migration in the 21st century.

2.3.2 UN Human Rights Law and Environmental Displacement

While refugee law offers limited utility, international human rights law provides broader protections—at least in theory. The Human Rights Committee, in its 2020 decision Teitiota v. New Zealand, recognized that returning someone to a country where climate change poses a real and foreseeable risk to their right to life could violate Article 6 of the ICCPR (Human Rights Committee, CCPR/C/127/D/2728/2016).¹² Although the Committee did not find that New Zealand had breached Mr. Teitiota’s rights in this case, it affirmed that climate-related threats can be legally relevant grounds for protection under human rights law.¹³ The case marked the first time an international human rights body explicitly acknowledged that environmental degradation could render a country uninhabitable—and therefore trigger state responsibility.

However, unlike refugee protection, human rights law does not grant a legal status or residency rights to displaced persons. It merely imposes negative obligations on states not to return people to life-threatening conditions. This limitation makes it a protective floor, not a holistic solution for climate migrants.

2.3.3 The Global Compact on Migration and Related Soft Law Instruments

In response to growing recognition of climate-driven mobility, the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM), adopted in 2018, explicitly acknowledges climate change as a driver of migration.[15] While not legally binding, the GCM calls on states to:

Develop comprehensive responses to displacement due to natural disasters and climate change;

Enhance regular migration pathways;

Strengthen data collection and early warning systems; and

Promote adaptive strategies to minimize forced migration.

The GCM is part of a growing body of soft law instruments including the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and the Cancún Adaptation Framework—that encourage international cooperation but lack binding enforcement.[16] Their influence is therefore normative rather than prescriptive, and implementation varies widely by region and political will. Southeast Asia, while a participant in GCM consultations, has yet to articulate a coordinated regional strategy that aligns with these global principles. This underscores the need for an ASEAN-specific legal and policy framework that translates soft law aspirations into concrete protections.

2.4 Legal Gaps in International Protection

Despite the growing urgency of climate-induced displacement, international law continues to operate under a fragmented, outdated paradigm. Key gaps include:

Lack of a legal definition for “climate migrant” or “environmental refugee” under any binding treaty;[17]

Absence of a binding multilateral instrument to govern cross-border climate displacement;

Inconsistent application of human rights standards, especially among Global South countries;

Overreliance on soft law, which lacks enforceability and often leaves implementation to national discretion.

In the Southeast Asian context, these global legal limitations are compounded by regional norms such as non-interference, weak institutional capacity, and a lack of refugee protection regimes in most member states. Without a collective framework, ASEAN countries risk adopting disparate, inconsistent, and often inadequate responses, further marginalizing vulnerable populations. The next chapter turns to Indonesia as a case study, exploring how one of the region’s most climate-exposed states is grappling with the legal and policy dimensions of internal displacement and cross-border migration, insights that will inform the broader goal of building a regional legal framework.

3: Southeast Asia and ASEAN: Vulnerabilities and Legal Readiness

3.1 Climate Vulnerability in Southeast Asia: A Regional Overview

Southeast Asia is both geographically diverse and ecologically rich, yet paradoxically among the most climate-vulnerable regions on the planet. From Indonesia’s sinking cities to Myanmar’s cyclone-battered coasts, from Vietnam’s saline-invaded rice fields to the Philippines’ typhoon corridors, climate change is no longer a distant threat—it is a lived reality.[18] This region is home to more than 670 million people, many of whom live in low-lying coastal zones, rely on agriculture for livelihoods, and lack adaptive infrastructure.[19]

According to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, Southeast Asia is experiencing rising average temperatures, increasing frequency of extreme weather events, coastal erosion, and severe flooding.[20] These effects are expected to intensify, particularly affecting poor and densely populated areas. The ASEAN State of Climate Change Report (2021) emphasizes that without coordinated mitigation and adaptation efforts, the region could suffer GDP losses of 11% by 2100.[21] The implications for migration are stark: the UNESCAP predicts that tens of millions in the Asia-Pacific will be displaced by climate-related events in coming decades.[22] In many ASEAN countries, climate mobility is already occurring, but remains largely invisible in official narratives and policies.

3.2 ASEAN Legal Instruments and Disaster Governance

ASEAN has long portrayed itself as a regional body committed to cooperation, resilience, and community. Yet, when it comes to legal instruments addressing human mobility under climate stress, its architecture remains fragmented and largely symbolic. ASEAN’s disaster governance regime is more developed than its climate mobility framework, and even that has notable limitations.

3.2.1 The ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response (AADMER)

Adopted in 2005 and entered into force in 2009, the ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response (AADMER) stands as the region’s only binding treaty on disaster cooperation.[23] AADMER aims to strengthen preparedness, early warning systems, response coordination, and recovery efforts among member states. It created the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on disaster management (AHA Centre) to operationalize regional response.

AADMER was hailed as a “milestone” for Southeast Asia, especially after the failures surrounding Cyclone Nargis in 2008, where Myanmar initially rejected international aid.[24] However, AADMER’s capacity to address cross-border climate-induced migration remains limited. It focuses on short-term disaster relief and does not explicitly recognize displacement or mobility as a long-term outcome of slow-onset climate events. Moreover, compliance is largely voluntary and dependent on political will.[25]

Critics argue that AADMER reflects the broader limitations of ASEAN’s institutional culture: progress is made only insofar as it does not challenge sovereignty.[26] While it formalizes cooperation, its implementation has been uneven, and it lacks mechanisms to address protection, relocation, or integration of displaced persons.

3.2.2 ASEAN Human Rights Declaration: Opportunities and Limitations

In 2012, ASEAN adopted the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD)—a non-binding commitment that recognizes fundamental rights including the right to life, health, and adequate standards of living.[27] While the AHRD offers a normative platform to discuss human security in the context of climate change, it has been criticized for its regressive caveats, including a general limitations clause that permits rights restrictions “as provided by law.”[28]

Critics argue that this clause gives ASEAN states too much discretion and weakens any claim to enforceable human rights obligations.[29] Moreover, the AHRD does not explicitly mention environmental degradation or displacement. As such, while it could be interpreted to protect climate-displaced persons under the broader right to life or dignity, such protections remain theoretical and unenforceable.

This reflects ASEAN’s general reluctance to elevate rights above sovereignty. Scholars note that while the AHRD symbolized progress in regional dialogue, it was the product of political compromise, and lacks teeth in influencing national policies or legislation.[30] While the AHRD lacks binding power, it represents a potential entry point for climate justice framing, especially through future interpretations by the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) or national human rights institutions.

3.3 Lack of Binding Mechanisms for Climate Displacement

Perhaps the most glaring gap in ASEAN’s legal framework is the absence of any binding regional instrument that recognizes or protects climate-induced migrants, especially those crossing borders. Climate-displaced persons do not qualify as refugees under the 1951 Refugee Convention, and ASEAN has not adopted any supplementary protections akin to Africa’s Kampala Convention.[31] Despite mounting evidence that environmental change is already displacing communities in the region, ASEAN has opted for soft-law approaches and generalized disaster frameworks that fail to address long-term human mobility. The Global Compact for Migration, which ASEAN supports, encourages the inclusion of climate migration in policy discussions,but again, it is non-binding.[32]

Scholars have called for ASEAN to take bolder steps, including drafting a regional protocol or action plan on climate displacement, grounded in human rights and environmental justice.[33] But to date, no such effort has materialized. Legal ambiguity persists, and affected populations remain legally invisible.

3.4 Regional Political and Legal Challenges

Any proposal for a regional climate migration framework must contend with ASEAN’s political DNA, rooted in the principles of non-interference and consensus. The ASEAN Charter enshrines these as foundational values,while promoting unity often lead to paralysis on sensitive issues like displacement or rights-based protections.[34] In practical terms, this means ASEAN avoids controversial topics and operates through lowest-common-denominator commitments.[35] Its regionalism is intergovernmental rather than supranational, and any legally binding mechanism that appears to encroach on national autonomy is met with resistance. This is evident in the Transboundary Haze Pollution Agreement, which took years to ratify and continues to suffer from weak enforcement.[36]

Moreover, ASEAN lacks a judicial or quasi-judicial body to enforce its declarations. Its legal landscape is fragmented, with environmental, human rights, and migration issues scattered across various institutions and declarations, none of which have binding force.[37] As a result, climate-induced migrants are not just environmentally displaced, but juridically neglected.

To overcome these challenges, ASEAN must reimagine its regional cooperation model, not by abandoning sovereignty, but by reconceptualizing it as collective responsibility in the face of shared existential threats. However, ASEAN’s precedent with the Transboundary Haze Pollution Agreement (2002)—despite enforcement issues—demonstrates that legal innovation is possible when diplomatic pressure and civil society engagement align. This momentum could be leveraged to push for a climate mobility agenda.

4. The Indonesian Case Study – A National Lens on Climate Displacement

Indonesia represents a powerful case study for examining climate-induced displacement in Southeast Asia. As the largest economy and most populous country in the ASEAN region and one that is exceptionally ecologically diverse and geographically fragmented makes Indonesia stand at the epicenter of environmental vulnerability. This section critically explores how climate-related drivers such as sea-level rise, floods, and deforestation intersect with legal and policy frameworks to influence internal displacement patterns. It also investigates how existing governance structures respond to climate mobility, with special attention to the rights and voices of Indigenous and coastal communities. Finally, this chapter offers reflections on what Indonesia’s experience can teach ASEAN about building a just and responsive regional approach.

4.1 Environmental Drivers of Displacement in Indonesia

The relationship between climate change and human mobility in Indonesia is complex and multidimensional. While it is difficult to isolate climate as a single causal factor of migration, evidence increasingly shows that environmental degradation is a growing push factor that intersects with poverty, land use change, urbanization, and governance failures. This section highlights two major environmental processes that are driving internal displacement in Indonesia: coastal inundation and ecological degradation from deforestation and flooding.

4.1.1 Sea-Level Rise and Sinking Cities: Jakarta, Semarang, and Beyond

Jakarta has become an international symbol of environmental risk. As a megacity situated on swampy land, burdened with poor drainage, unregulated urban growth, and heavy dependence on groundwater, Jakarta is sinking by as much as 10–17 centimeters annually in some areas.[38] This phenomenon—subsidence—is compounded by rising sea levels associated with climate change. The World Bank has identified Jakarta as one of the world’s most at-risk coastal cities, with projections estimating that 95% of North Jakarta could be submerged by 2050 without intervention.[39]

In response, the Indonesian government has launched a monumental plan to relocate its capital to Nusantara, a new site in East Kalimantan.[40] While this move has been officially justified as a strategy to reduce congestion and decentralize governance, climate adaptation and resilience are key motivations. However, this "managed retreat" model raises normative questions: Who gets to move? Who is left behind? What obligations exist to support vulnerable communities that cannot relocate so easily?

Jakarta is not alone. Cities like Semarang, Pekalongan, and Demak along Java’s northern coast are increasingly affected by tidal flooding (rob), saltwater intrusion, and coastline erosion.[41] According to the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (2022), Semarang experiences sea-level rise at a rate of 0.8 cm/year, compounded by 4–5 cm/year of land subsidence in affected areas. In Semarang, rising tides have rendered some neighborhoods permanently inundated, forcing households to abandon their homes or live in unsafe, degraded conditions.[42] Unlike sudden-onset disasters such as tsunamis, these slow-onset events are difficult to categorize and respond to, both politically and legally. The lack of early warning, insurance, or compensation mechanisms leaves many displaced people in informal settlements with limited state support.

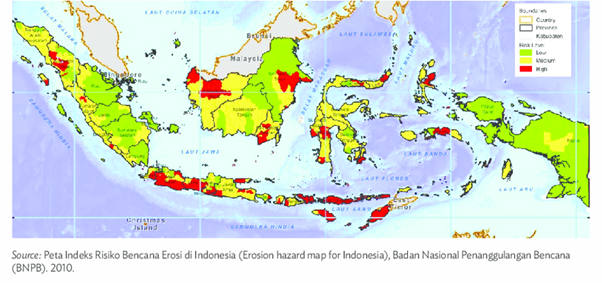

4.1.2 Deforestation, Floods, and Internal Migration

Beyond coastal regions, deforestation and land degradation play a significant role in triggering environmentally induced migration. Indonesia has one of the highest rates of deforestation globally, losing millions of hectares of forest primarily due to palm oil cultivation, mining, and logging.[43] This has directly increased the frequency and severity of floods and landslides across the archipelago.

In areas like Kalimantan and Sumatra, extensive peatland drainage and burning not only destroy ecosystems but also contribute to respiratory crises and livelihood loss. In 2015 and 2019, forest fires displaced thousands of people and created health emergencies that spanned national borders.[44] These events reveal the failure to regulate land use and prevent overlapping environmental, social, and public health crises.

Inland floods, exacerbated by deforestation, poor watershed management, and more intense rainfall have become common in Central Java, South Sulawesi, and Papua.[45] These hazards often disproportionately affect poor, rural, and Indigenous populations. Because such communities lack formal land tenure or economic resilience, they are frequently relocated with limited consent or compensation. Meanwhile, secondary migration flows are emerging, as displaced rural populations move to already overburdened urban centers, creating new pressures on infrastructure and social services.[46]

4.2 National Legal Framework and Policy Gaps

Indonesia’s legal and policy framework for addressing climate displacement remains fragmented and underdeveloped. While several legal instruments reference disaster response and climate adaptation, none provide an integrated framework that addresses climate-induced displacement as a distinct legal category. This institutional invisibility is particularly concerning given the scale and complexity of the challenges ahead.

Law No. 24/2007 on Disaster Management provides the primary legal basis for responding to natural disasters.[47] However, the law focuses predominantly on short-term emergency response and post-disaster recovery. It does not cover slow-onset processes such as sea-level rise or drought, nor does it offer procedural guarantees for the rights of displaced persons.

Similarly, Law No. 32/2009 on Environmental Protection and Management incorporates climate resilience as a guiding principle but lacks enforceable obligations for government agencies to address population displacement caused by environmental change.[48] Indonesia’s climate planning documents—such as its National Adaptation Plan (NAP) and its National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2020–2024 acknowledge climate impacts but fail to define or protect the rights of displaced persons.[49]

This legal vacuum results in governance fragmentation. Different ministries, such as the Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Social Affairs, and National Disaster Management Agency approach displacement from different lenses (environmental, welfare, emergency), without coherent coordination.[50] There are no national guidelines for planned relocation, no eligibility criteria for support, and no monitoring mechanisms to track displacement due to environmental change. The absence of a binding, intersectoral legal framework renders climate-displaced persons vulnerable to bureaucratic neglect and institutional confusion.

4.3 Indigenous and Coastal Communities: A Human Rights Perspective

Among those most impacted by climate displacement in Indonesia are Indigenous and coastal communities, many of whom already suffer from legal marginalization and weak tenure security. For Indigenous groups, land is not just a resource—it is a relational, spiritual, and cultural foundation. Displacement thus carries not only physical and economic costs, but also existential trauma.

The 2012 Constitutional Court Decision No. 35/PUU-X/2012 was a landmark ruling recognizing hutan adat (customary forests) as distinct from state forests.[51] While celebrated as a legal breakthrough, its implementation remains slow and uneven. Many Indigenous communities lack the administrative capacity or political support to register their lands, leaving them vulnerable to state appropriation, corporate encroachment, or climate-driven relocation without consent.

In climate adaptation projects such as seawalls, mangrove restoration, or eco-tourism zones many communities are relocated without free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), violating international human rights norms.[52] In these processes, women , especially those in small-scale fisheries and aquaculture—are often excluded from decision-making, even though they carry the burden of sustaining household resilience.[53] For example, in Kendari and Merauke, Indigenous land has been reclassified as development zones without adequate consultation. This contravenes FPIC obligations under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), to which Indonesia has expressed commitment.

Climate justice demands more than technocratic solutions—it requires an inclusive governance model that recognizes the historical injustices, social hierarchies, and structural inequalities that shape vulnerability. Indigenous worldviews must be treated not as obstacles to modern governance, but as rich epistemologies that can inform more just and sustainable adaptation.

4.4 Lessons for Regional Adaptation and Resilience

Indonesia’s experience offers ASEAN a compelling set of lessons. First, the sheer scale of internal displacement driven by both sudden and slow-onset climate events demonstrates the urgency of legal recognition for climate-induced migration. Second, the case shows the risks of relying on fragmented governance and soft law. Without a coordinated legal framework, the displaced fall into procedural limbo. Third, and perhaps most critically, Indonesia illustrates the need for a rights-based, participatory approach to climate adaptation.

The lived realities of Indigenous and coastal communities challenge top-down models and call for inclusive policymaking rooted in justice, consent, and cultural continuity. ASEAN must view Indonesia not only as a climate frontline but as a laboratory of governance experimentation where resilience is contested, negotiated, and constantly evolving. A future regional framework must reflect this complexity, ensuring that no one is left behind in the face of a changing climate.

5. Comparative Insights: Other ASEAN Member States

Indonesia’s experience with climate displacement is illuminating, but it does not exist in a vacuum. The ASEAN region comprises highly climate-vulnerable nations, each grappling with environmental threats that are forcing people from their homes. A regional legal framework must be rooted not in abstraction, but in the tangible realities of the people most affected. This section offers comparative insights from Vietnam, the Philippines, and briefly Bangladesh (a close ASEAN neighbor and frequent point of policy influence), to identify legal patterns, good practices, and opportunities for harmonization in Southeast Asia’s fragmented legal terrain.

5.1 Case Snapshots: Vietnam, the Philippines, and Bangladesh

a. Vietnam

Vietnam’s Law on Natural Disaster Prevention and Control (2013) includes provisions on resettlement, but these are not framed within a rights-based discourse. Most relocations focus on physical safety rather than legal protection or livelihood restoration. Vietnam ranks among the top five countries globally most threatened by sea-level rise.[54] Its Mekong Delta region home to over 17 million people is experiencing saline intrusion, coastal erosion, and reduced agricultural productivity.[55] Vietnam has already begun relocating thousands of households away from flood-prone deltas through government-managed adaptation projects. However, while the relocations are organized, they often lack meaningful consultation, triggering issues of consent, compensation, and cultural dislocation.[56]

b. The Philippines

The Philippines experiences some of the world’s most severe climate disasters, averaging 20 typhoons per year.[57] Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) in 2013 displaced over 4 million people, many of whom remain in temporary or precarious housing.[58] The government has developed Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) systems and incorporated climate risk into urban planning.[59] However, it has no legal category for climate-displaced persons, and local governments frequently struggle to operationalize national guidelines. Land tenure, poverty, and bureaucratic capacity remain critical barriers to durable solutions.[60]

c. Bangladesh (for context and comparison)

While not an ASEAN member, Bangladesh’s experience is often cited in Southeast Asian forums. It faces mass displacement from riverbank erosion, sea-level rise, and cyclones.[61] Remarkably, it has adopted a National Strategy on the Management of Disaster and Climate-Induced Internal Displacement (2015) a pioneering document that explicitly addresses internal climate migration and relocation.[62] Though implementation challenges remain, Bangladesh offers an important regional benchmark for integrating displacement into legal and policy frameworks. Despite its forward-looking strategy, implementation suffers from lack of coordination between the Ministry of Disaster Management and grassroots authorities, revealing the limits of soft law in the absence of binding commitments.

5.2 National Responses to Climate Displacement

While each of these countries is acutely aware of climate risk, their legal and policy responses remain uneven and largely incomplete.

a. Vietnam has embedded climate mobility into certain policies, such as the National Strategy on Climate Change and the Law on Natural Disaster Prevention and Control (2013). However, these laws primarily focus on disaster response rather than long-term mobility planning.[63] Community relocation is framed more as infrastructure policy than as a rights-based approach to displacement.[64]

b. The Philippines has developed an advanced DRRM legal framework under Republic Act No. 10121 (2010), establishing institutional coordination for disaster preparedness and response.[65] The Climate Change Act of 2009 mandates mainstreaming climate risk into local planning.[66] Yet both laws stop short of recognizing climate displacement as a specific legal or social phenomenon. National housing programs and emergency aid cover affected persons, but they lack sustained relocation mandates or accountability structures.[67]

c. Bangladesh, by contrast, explicitly defines climate-induced displacement in its national strategy, identifying affected groups and proposing relocation, land access, and livelihood restoration schemes.[68] Though the strategy lacks binding force, its conceptual clarity could serve as a model for ASEAN states still grappling with the definitional and legal vacuum.

5.3 Opportunities for Legal Harmonization Across ASEAN

Despite the diverse legal systems in the region ranging from civil law (Vietnam), mixed systems (Philippines), and Islamic legal influences (Brunei, Indonesia)—ASEAN states share several points of convergence that could support legal harmonization on climate displacement. All ASEAN states are highly exposed to climate threats, particularly coastal flooding, typhoons, and drought. This shared context can form the basis for regional solidarity, particularly in building a common language around displacement. Frameworks like AADMER already facilitate disaster coordination. While AADMER currently excludes slow-onset disasters and legal protection mandates, it can be amended or expanded to include climate displacement criteria. Many national climate laws and plans mention resilience, adaptation, and disaster response—though not always coherently. A regional framework could harmonize definitions of displaced persons, minimum relocation standards, and rights guarantees.

Legal instruments to build on:

○ ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (2012)

○ AADMER (2005)

○ Global Compact for Migration (GCM), to which most ASEAN members are parties.

A regional treaty or protocol could define climate-displaced persons, establish non-refoulement protections, articulate resettlement principles, and guide funding mechanisms through ASEAN’s Climate Resilience Fund or AHA Centre coordination.

6. Toward an ASEAN Legal Framework for Climate-Induced Migration

6.1 Principles for a Regional Framework: Human Rights, Climate Justice, and Shared Responsibility

Any regional framework on climate-induced displacement must begin by articulating a clear normative foundation—one rooted not only in legal theory, but in justice and empathy for those most affected. Three interdependent principles stand out.

At its core, displacement is not simply a movement issue—it is a human rights issue. Climate-induced migrants are often denied access to housing, land, health care, education, and political representation. The ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (2012) reaffirms these rights, including the right to life, an adequate standard of living, and protection against forced evictions.[69] A regional framework must guarantee that such rights are protected during all phases of displacement: before, during, and after people are forced to move. Climate justice recognizes that those most affected by climate change are often those least responsible for causing it. Across ASEAN, Indigenous peoples, subsistence farmers, women, children, and coastal dwellers face compounded vulnerability due to both climate exposure and systemic marginalization.[70] A rights-based framework must center their voices—not as passive recipients of aid, but as active participants in designing solutions. This requires moving beyond technocratic risk management to prioritize historical equity and intergenerational justice.

Climate-induced displacement transcends national borders. Sea-level rise, for example, affects the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, the northern coasts of Java, and the southern shores of the Philippines. Yet current responses remain largely national in scope. ASEAN must adopt a model of collective resilience, recognizing that no single state can manage climate displacement alone.[71] Shared responsibility does not mean abandoning sovereignty—it means enhancing it through regional solidarity.

6.2 Legal Design Options: Treaty, Protocol, or Guiding Principles?

ASEAN’s legal architecture is evolving. While known for its soft law approach, ASEAN has adopted binding instruments on matters like disaster response and environmental cooperation. The same can be done for climate mobility. Three design models are available.

A. Legally Binding Treaty or Protocol

A binding regional protocol on climate-induced displacement either standalone or as a protocol to the AADMER would represent a groundbreaking step. Modeled on Africa’s Kampala Convention,[72] it could legally define climate-displaced persons, articulate state obligations for protection and relocation, and establish monitoring mechanisms. The protocol could include provisions for:

Voluntary and informed relocation

Minimum standards for shelter, livelihood restoration, and cultural preservation

Regional funding pools and technical assistance

B. Guiding Principles or Declaration

Alternatively, ASEAN could adopt non-binding principles, similar to the Nansen Initiative’s Protection Agenda, which offers a soft law framework for cross-border displacement due to disasters and climate change.[73] This format would be easier to negotiate and could serve as a stepping stone toward future binding commitments. It would also allow for experimentation and norm-building, particularly in politically sensitive areas.

C. Hybrid Model

ASEAN may also adopt a phased approach: beginning with a declaration, followed by institutionalization through ministerial meetings, and finally codifying a treaty or protocol. This gradualism is consistent with ASEAN’s legal tradition and “ASEAN Way”, which privileges consensus and incrementalism.[74]

6.3 Role of ASEAN Intergovernmental Bodies

ASEAN already possesses a rich institutional ecosystem that can support a climate mobility framework, provided it is properly mobilized and integrated:

ASEAN Secretariat: Acts as the primary coordinating body. It should host a dedicated Climate Mobility Unit to oversee legal harmonization, facilitate capacity building, and monitor implementation.[75]

ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance (AHA Centre): Currently focused on disaster response, the AHA Centre could expand its mandate to include slow-onset displacement, displacement tracking systems, and emergency relocation logistics.

ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR): Although lacking enforcement power, AICHR can issue interpretive statements, conduct impact assessments, and ensure that member state practices align with ASEAN’s human rights commitments.[76]

ASEAN Working Group on Climate Change: Can support integration of mobility into climate planning and develop technical guidelines for resettlement, livelihood recovery, and environmental restoration.

ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) and civil society networks should also be engaged to ensure inclusive policymaking.

ASEAN should also develop a Stakeholder Engagement Matrix identifying key actors, potential champions (e.g., Indonesia, the Philippines), and likely resistors (e.g., Cambodia, Myanmar), helping to forecast diplomatic dynamics in treaty negotiations. A Cross-Pillar Climate Mobility Task Force, composed of representatives from ASEAN’s political-security, socio-cultural, and economic pillars, could foster coordination across sectors and mandates.

6.4 Potential Challenges and Implementation Barriers

Despite the compelling need, several political and legal hurdles must be acknowledged:

Sovereignty Concerns: ASEAN’s long-standing principle of non-interference can hinder efforts to establish binding regional standards.[77] Member states may resist what they perceive as external scrutiny or legal encroachment.

Legal Fragmentation: Across the region, displacement is managed through disaster laws, environmental statutes, and social welfare policies, often without coordination or legal clarity on migration.

Institutional Limitations: Bodies like AICHR lack investigative authority. Others, like the AHA Centre, lack a human rights mandate. ASEAN’s consensus-based model also makes decision-making slow and incremental.

Resource Constraints: ASEAN countries vary widely in capacity. Least developed members like Laos, Cambodia, or Myanmar may struggle to meet obligations without financial or technical support.

Data Gaps: Most ASEAN states lack comprehensive data on climate displacement trends, making evidence-based policymaking difficult.

Yet, these are not insurmountable challenges. Similar resistance preceded the Transboundary Haze Pollution Agreement and AADMER. Political will, donor engagement, and civil society pressure have proven effective in overcoming inertia when human suffering is visible and urgent.

6.5 Policy Recommendations for ASEAN and Member States

To build momentum and achieve legal coherence, ASEAN and its member states should take the following steps:

1. Draft and Adopt an ASEAN Declaration or Protocol on Climate-Induced Displacement

This instrument should clearly define climate-displaced persons, outline minimum standards for protection, and include implementation guidelines for relocation and durable solutions.

2. Amend AADMER to Include Climate Displacement

AADMER can be updated to explicitly include slow-onset events like sea-level rise and drought, along with human mobility as an adaptation strategy.

3. Establish a Climate Mobility Task Force

Housed under the ASEAN Secretariat, this body would support legal harmonization, coordinate across sectors, monitor state implementation, and engage with external partners.

4. Institutionalize Community Participation

ASEAN must guarantee the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) of communities in all climate displacement planning, particularly Indigenous and coastal groups. Regional frameworks should incorporate gender-sensitive, rights-based, and culturally appropriate guidelines.

5. Create a Regional Climate Mobility Fund

This fund would support member states in conducting vulnerability assessments, financing relocation infrastructure, and protecting displaced persons. It could be financed through ASEAN contributions, international donors, and climate financing mechanisms.

6. Establish a Regional Displacement Observatory

ASEAN should create a centralized data repository to monitor climate displacement trends, supported by the AHA Centre and regional universities. This evidence base is essential for adaptive policymaking and early intervention.

Conclusion

This research has critically examined the legal, institutional, and normative gaps surrounding climate-induced migration in Southeast Asia, with Indonesia serving as a microcosm of the region’s broader vulnerabilities and policy inertia. It finds that despite growing climate displacement across the ASEAN region—driven by both slow-onset environmental changes and sudden disasters—there remains no coherent or binding legal framework to protect those most affected.

Indonesia, while deeply exposed to sea-level rise, flooding, and deforestation, lacks a legal category for climate-displaced persons. Its disaster and environmental laws are reactive, fragmented, and silent on long-term relocation or adaptation. Meanwhile, ASEAN’s regional instruments—particularly AADMER and the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration offer useful starting points but fall short of addressing the legal invisibility of those displaced by climate change.

Comparative insights from Vietnam, the Philippines, and Bangladesh reveal that while policy attention to climate vulnerability is growing, legal recognition of climate-induced displacement remains limited. Bangladesh stands out for adopting a dedicated national strategy, but even this remains non-binding. The comparative landscape demonstrates a critical opportunity for ASEAN to craft a regionally grounded, justice-based legal framework that reflects the shared risk and common humanity of its peoples.

This research offers both conceptual and policy-level contributions to the emerging field of climate mobility law. From a scholarly perspective, it advances the understanding of climate-induced migration as a legally under-recognized yet normatively urgent category. It challenges the traditional bifurcation of forced and voluntary migration, showing that climate mobility often lies within a grey zone of constrained agency. It also contributes to the growing scholarship that calls for regional legal innovation in the Global South,especially in regions, like ASEAN, where binding legal instruments remain scarce but socio-ecological risk is high.

From a policy perspective, the thesis provides a concrete roadmap for ASEAN to move beyond symbolic commitments. It identifies institutional entry points (e.g., AADMER, AICHR), outlines feasible legal instruments (e.g., protocols, guiding principles), and proposes actionable policy tools—from FPIC mechanisms to regional funding pools. The proposed legal framework is grounded not just in theory, but in the lived realities of communities already experiencing displacement.

Moreover, by centering Indonesia’s national experience, this research ensures that legal design is informed by practice, not imposed from above but shaped from below. It argues that ASEAN’s strength lies not in mimicking Global North models, but in crafting a legal response that reflects its political culture, socio-ecological diversity, and collective ethos.

Climate change is not a distant risk. It is a lived, accelerating reality—already forcing thousands across Southeast Asia to leave ancestral lands, lose livelihoods, and rebuild lives in unfamiliar places. The law, if it remains silent or rigid, becomes complicit in this suffering. But if it evolves—expanding its protective reach, reimagining its categories, and listening to those it has historically excluded—it can become a vehicle for dignity, resilience, and justice.

Reimagining legal protection in the climate era means shifting from statelessness to solidarity, from legal invisibility to human rights visibility, from state-centric sovereignty to shared regional stewardship. It means recognizing that the climate crisis is also a legal crisis one that demands bold, collective responses from institutions that were never designed for a warming world.

ASEAN now faces a defining choice. It can continue to treat climate-induced migration as a marginal outcome of disaster response—or it can lead innovatively, crafting a regional legal framework that elevates human dignity, resilience, and solidarity. This research urges ASEAN to transform legal invisibility into protection, and policy inertia into proactive stewardship in the face of a climate-challenged future.

[1] Scott A. Kulp & Benjamin H. Strauss, New Elevation Data Triple Estimates of Global Vulnerability to Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Flooding, 10 Nat. Commc’ns 4844 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z.

[2] Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, July 28, 1951, 189 U.N.T.S. 137; Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, Jan. 31, 1967, 606 U.N.T.S. 267.

[3] Charter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations art. 2(2)(e), Dec. 15, 2008, https://agreement.asean.org/media/download/20160509062115.pdf.

[4] International Organization for Migration [hereinafter IOM], Discussion Note: Migration and the Environment, MC/INF/288 (Nov. 1, 2007), https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/migrated_files/What-We-Do/docs/Migration-and-the-Environment.pdf.

[5] Jane McAdam, Climate Change, Forced Migration, and International Law 7–12 (Oxford Univ. Press 2012).

[6] Koko Warner et al., In Search of Shelter: Mapping the Effects of Climate Change on Human Migration and Displacement 8–9 (United Nations Univ. Inst. for Env’t & Human Sec. 2009), https://www.ehs.unu.edu/file/get/3975.pdf.

[7] IOM, Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Assessing the Evidence 12–18 (2009), https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/migration_and_environment.pdf.

[8] Alex de Sherbinin et al., Climate Change and the Risk of Statelessness: The Situation of Low-Lying Island States, UNHCR Legal & Prot. Pol’y Rsch. Series 14–16 (2011), https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/protection/globalconsult/4df9cb0c9/climate-change-risk-statelessness-situation-low-lying-island-states.html.

[9] Mary Robinson, Climate Justice: Hope, Resilience, and the Fight for a Sustainable Future 33–40 (Bloomsbury 2018).

[10] Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, July 28, 1951, art. 1(A)(2), 189 U.N.T.S. 137; Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, Jan. 31, 1967, 606 U.N.T.S. 267.

[11] U.N. Commission on Human Rights, Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, U.N. Doc. E/CN.4/1998/53/Add.2 (Feb. 11, 1998).

[12] François Gemenne, Climate-Induced Population Displacements in a Global North–South Perspective, in Climate and Soc’y: Climate as a Res., Climate as a Risk 13–24 (M. Hulme ed., Routledge 2009)

[13] Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, July 28, 1951, art. 1(A)(2), 189 U.N.T.S. 137; Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, Jan. 31, 1967, 606 U.N.T.S. 267.

[14] U.N. High Commission for Refugees [hereinafter UNHCR], Legal Considerations Regarding Claims for International Protection Made in the Context of the Adverse Effects of Climate Change and Disasters ¶¶ 5–9

[15] G.A. Res. 73/195, Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, ¶ 18 (Dec. 19, 2018), https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/73/195.

[16] U.N. Office for Disaster Risk Reduction [UNDRR], Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, ¶¶ 27–30 (Mar. 18, 2015); U.N.F.C.C.C., Cancún Adaptation Framework, Dec. 11, 2010, in Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Sixteenth Session, Addendum, U.N. Doc. FCCC/CP/2010/7/Add.1.

[17] Walter Kälin & Nina Schrepfer, Protecting People Crossing Borders in the Context of Climate Change: Normative Gaps and Possible Approaches, UNHCR Legal & Prot. Pol’y Rsch. Series (Feb. 2012), https://www.refworld.org/docid/4f38a9422.html.

[18] IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability – Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report, ch. 10, at 1431–33 (2022).

[19] ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN State of Climate Change Report 18–22 (Jakarta 2021), https://asean.org/book/asean-state-of-climate-change-report/.

[20] Id.

[21] Id. at 40–41.

[22] U.N. Economic & Social Commission for Asia & Pacific, Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2022 33 (2022), https://www.unescap.org/resources/asia-pacific-disaster-report-2022.

[23] ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response, July 26, 2005, entered into force Dec. 24, 2009, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/AADMER.pdf.

[24] Gabrielle Simm, Disaster Response in Southeast Asia: The ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response, 8 Asian J. Int’l L. 116, 122–24 (2018).

[25] Id. at 128–30.

[26] Brooke N. Coe & Kilian Spandler, Beyond Effectiveness: The Political Functions of ASEAN’s Disaster Governance, 28 Global Governance 355, 359–63 (2022).

[27] ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, Nov. 18, 2012, reprinted in ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Hum. Rts. Declaration and Phnom Penh Statement 2 (2013).

[28] Gerard Clarke, The Evolving ASEAN Human Rights System, 11 Nw. J. Int’l Hum. Rts. 1, 8–10 (2012).

[29] Id.

[30] Mathew Davies, An Agreement to Disagree: The ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, 33 J. Current Se. Asian Aff. 107, 109–12 (2014).

[31] Evan M. FitzGerald & Gregory G. Toth, Nowhere to Go: A Regional Human Rights-Based Approach to Climate Displacee Protection, 31 Wash. Int’l L.J. 213, 218–24 (2022).

[32] G.A. Res. 73/195, Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, ¶ 18 (Dec. 19, 2018

[33] FitzGerald & Toth, supra note 31, at 225–31.

[34] Charter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations art. 2(2)(e), Nov. 20, 2007, 2624 U.N.T.S. 223.

[35] Shaun Narine, ASEAN in the Twenty-First Century: A Skeptical Review, 22 Camb. Rev. Int’l Aff. 369, 372–75 (2009).

[36] Sanae Suzuki, Interfering via ASEAN? Disaster Management and the Limits of Non-Interference, 40 J. Current Se. Asian Aff. 400, 410–12 (2021).

[37] Amitav Acharya, Constructing a Sec. Cmty. in Se. Asia 50–55 (3d ed. 2014).

[38] UNDRR, Indonesia: Disaster Risk Profile (2022), https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/indonesia-disaster-risk-profile.

[39] World Bank, Indonesian Coastal Cities at High Risk (Apr. 28, 2021), https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/04/28/indonesia-s-coastal-cities-at-high-risk.

[40] Indonesia to Move Capital from Jakarta to East Kalimantan, BBC News (Aug. 26, 2019), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-49470614.

[41] Asian Develpoment Bank, Building Urban Resilience in Semarang (2020), https://www.adb.org/publications/building-urban-resilience-semarang.

[42] Id.

[43] Global Forest Watch, Indonesia Country Dashboard (2022), https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/IDN/.

[44] Id.

[45] World Bank, Indonesian Cities: Urbanization and Climate Risks (Mar. 1, 2021), https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/03/01/indonesian-cities-urbanization-and-climate-risks.

[46] Id.

[47] Law No. 24 of 2007 on Disaster Mgmt. (Indonesia), art. 47.

[48] Law No. 32 of 2009 on Env’t Prot. and Mgmt. (Indonesia), arts. 1–3.

[49] Republic of Indonesia, National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2020–2024, Bappenas, https://www.bappenas.go.id/show-result-satudata?name=publikasi&key=rpjmn&tahun=

[50] Id.

[51] Const. Ct. Decision No. 35/PUU-X/2012 (Indonesia), https://en.mkri.id/download/decision/pdf_Decision_35PUU-X2012.pdf.

[52] Marcus Colchester et al., Oil Palm Expansion in Se. Asia: Trends and Implications for Indigenous Peoples 57–64 (Marcus Colchester & Sophie Chao eds., Forest Peoples Programme 2011), https://www.forestpeoples.org/en/node/50229.

[53] Oxfam Indonesia, Gender and Climate Just. in Coastal Cmtys. (2021), https://www.oxfam.or.id/publikasi.

[54] Asian Development Bank, Addressing Climate Change and Migration in Asia and the Pacific 11 (2012), https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/29662/addressing-climate-change-migration.pdf.

[55] IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, ch. 10 (Asia), at 1467 (2022), https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/.

[56] Dun, Olivia, & Benjamin L. Smith, Formalizing Climate Migration: Legal and Policy Developments in Vietnam, 14 Asian-Pac. Migration J. 55, 60–62 (2018).

[57] UNDRR, Philippines: Disaster Risk Profile (2020), https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/philippines-disaster-risk-profile.

[58] Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), Displacement Associated with Typhoon Haiyan, IDMC Report (2014), https://www.internal-displacement.org.

[59] Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010, Rep. Act No. 10121 (May 27, 2010), https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2010/05/27/republic-act-no-10121/.

[60] U.N. Development Programme, Resilient Urban Governance in the Philippines: Gaps and Opportunities 27 (2019).

[61] World Bank, Groundswell Part II: Acting on Internal Climate Migration 87–90 (2021), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36248.

[62] Goverment of Bangladesh, Nat’l Strategy on the Mgmt. of Disaster and Climate Induced Internal Displacement (2015) [hereinafter Bangladesh National Strategy], https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/national-strategy-management-disaster-and-climate-induced-internal-displacement.

[63] Law No. 33/2013 on Nat. Disaster Prevention and Control (Viet.), arts. 5, 18.

[64] CARE International, Relocation and Resettlement in the Context of Climate Change: The Case of Vietnam (2017), https://careclimatechange.org.

[65] Republic Act No. 10121, supra note 59.

[66] Climate Change Act of 2009, Rep. Act No. 9729 (Oct. 23, 2009) (Phil.), https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/advanced-search/?document_search=9729&document_type=executive-issuances.

[67] IDMC, Philippines Country Profile: Climate and Conflict-Induced Displacement (2022), https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/philippines.

[68] Bangladesh National Strategy, supra note 52, at 5–9.

[69] ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, Nov. 18, 2012, reprinted in ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Human Rights Declaration and Phnom Penh Statement 2 (2013).

[70] Mary Robinson Foundation-Climate Justice, Principles of Climate Justice (2011), https://www.mrfcj.org/principles-of-climate-justice/.

[71] ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Socio-Cultural Cmty. Blueprint 2025 (Jakarta 2016), https://asean.org/book/asean-socio-cultural-community-blueprint-2025/.

[72] African Union, Kampala Convention on the Prot. and Assistance of Internally Displaced Pers. in Africa (Oct. 23, 2009), 52 I.L.M. 597.

[73] Nansen Initiative, Agenda for the Prot. of Cross-Border Displaced Pers. in the Context of Disasters and Climate Change (2015), https://www.nanseninitiative.org.

[74] Simm, supra note 24, at 123.

[75] ASEAN Charter art. 13, Nov. 20, 2007, 2624 U.N.T.S. 223.

[76] Rebecca Barber, Why a Regional Agreement on Climate Displacement is Essential for ASEAN, 22 Int’l J. Refugee L. 276, 279–81 (2021).

[77] Shaun Narine, ASEAN in the Twenty-First Century: A Skeptical Review, 22 Camb. Rev. Int’l Aff. 369, 372–75 (2009).